By Philippe TRIAY

The unfortunate « blackface » of the famous French soccer player Antoine Griezmann ten days ago, an incident that dominated the French press and social media for several days, following the exclusion of anti-racist activist Rokhaya Diallo of the Digital National Council by the government, recently triggered controversy and new debates on the issue of racism in France. Maybe it’s time to talk about it from another perspective.

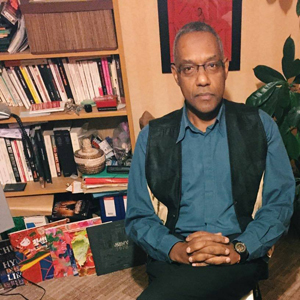

I was born and raised in the South of France in the sixties. My mother, born also in the South, is French-Malian. My father, who has since passed away, was from Martinique, a former French slave colony in the West Indies that has become a « French department » since 1946. My mother’s father arrived in France from his native Mali in the 1910s, as a servant of a colonial administrator who was returning home.

This southern France where I lived as a child did not resemble anything of what I read about the South of the United States at that time, when blacks were discriminated at the institutional level and often horribly lynched. I attended public school with my little white classmates. Throughout my schooling, I was mostly the only black youth in my class. There were also some students of North African origin. No legal segregation, no lynching (although many North Africans were victims of « ratonnades », violent physical attacks by groups of whites), but many racist remarks. « Nigger », « coon », « gook », and many others, are insults that I heard during all throughout my youth.

The French love to criticize racism elsewhere, especially American racism. Historically, black Americans found an attentive ear in France. The most famous, Richard Wright, Chester Himes, James Baldwin (who settled in the South of France and whom I had the great honor to know), Toni Morrison, Angela Davis, Black Panthers like Eldridge Cleaver and more recently the successful writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, became the darlings of some of the French intelligentsia. To be more precise, the Parisian intelligentsia, because the rest of the country does not really care.

Same thing for a lot of artists and musicians, such as Josephine Baker, Miles Davis, Archie Shepp, Dee Dee Bridgewater and so many others adored by the French. Films denouncing American racism have always had wide open doors in France: Spike Lee, with « Do The Right Thing » and « Malcolm X »; more recently « Selma », « Twelve Years A Slave », « The Birth of A Nation » by Nate Parker, « Detroit », to name but a few, have been very successful.

Yes, this France, which proclaims itself « the country of human rights » to the entire world, loves to identify racism and discrimination anywhere but at home. Yet, within its borders, there are so many problems. Certainly there has been progress. During my student years in the 80s, I never imagined one day seeing a black minister of Justice in France, Christiane Taubira, born in French Guiana, succeeding her predecessor Rachida Dati, born of North African parents, or a minister of Education, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, of Moroccan origin, or Fleur Pellerin, minister of Culture of Korean origin. And others belonging to « minorities » who have climbed the steps of the summits of the State (ministerial advisers, ambassadors, high-ranking officials, parliamentarians, etc.). Not to mention the other advances in the economic, scientific, associative, sports, media and culture fields.

This is why I reject the expressions « state racism » or « institutional racism » used by some activists to denounce France. It only radicalizes the debate in a caricatural and manichean way without accomplishing anything. That being said, our country must now recognize its flaws.

An imperialist, slave and colonial country, France ruled for centuries over a large part of the world: North, West and Central Africa, of East Africa, Madagascar, Mauritius and the Comoros in the Indian Ocean, the former French Indochina including Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos, and the Caribbean, which included until 1804 a flourishing Haiti in the sugar industry that contributed to the wealth of France. Currently, Paris has nine colonies disguised as “departments” or “territories”, spread over all continents and making France the second largest maritime and strategic world power: Guadeloupe, Guiana, Martinique, Mayotte, New Caledonia, French Polynesia, Reunion, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, Wallis and Futuna, plus the French Arctic and Antarctic Lands, all of which represent more than 2.7 million people and millions of square kilometers.

The majority of French people are not aware of the immeasurable contribution of these ex or current colonies to the development of the French economy, industry and finance. Successful and bourgeois cities like Bordeaux, Nantes, La Rochelle, Le Havre and many others would never have known such fortune and prosperity without slavery and colonization, for example. In fact, our system has failed due to lack of pedagogy and proactive and inclusive policies, particularly in terms of national education, media and culture. As a result, the French know practically nothing about the parts of their past that are problematic: these troubled and still under-explored areas of history, where the extreme violence of colonialism has literally wiped out peoples and communities.

With its usual hypocrisy, through the laziness of elites and political leaders, its intellectual cowardice and devious racism, France is sinking a little deeper into a worrisome situation. Aside from the blackface affair that has recently excited the press, the people and especially the youth victims of discrimination in many areas (employment, housing and culture in particular) are fed up with exclusion. They are also tired of police provocation and violence against them.

Moreover, following the terrorist attacks perpetrated by its own nationals, mostly of North African origin, France does not seem to have understood that perpetuating situations of inequality, contempt and exclusion can only lead some people to radicalization and extremism, of course exploited by organizations with specific agendas. For now, it is clear that the French government’s response is not up to the task.

Philippe TRIAY (Pluton-Magazine/2017)

News reporter for France Televisions. Author of « For A Fanonian Reading Of Césaire » (essay, Editions Dagan, April 2015), and « Barbaries » (poetry, Editions du Manguier, February 2016).