.

By Rose Marie BARRIENTOS

.

Although argumentation is rooted in ancient Greece, its study may be described as emergent, or even as a “work-in-progress”. My choice of words is not innocent, of course. Coming from the art world into Argumentation studies, I see the landscape around me as one that has often changed, its actors challenging previous concepts and theories, piling layer upon layer of opinions, interpretations, controversies, and, of course, knowledge. Without wanting to overdramatize my experience, I would replace “landscape” with “outer space” to characterize my first steps in what is for me a totally new domain, a space where concentration and caution are in order, but also a space where daring plunges into unknown territory are occasionally encouraged, and expected. This paper is one of those open spaces, a rather intimidating one at first, it must be said, but also tempting. I shall therefore take the plunge and examine Stephen Toulmin’s central contribution to Argumentation theory, the Toulmin Model, zooming in on his diagram, which is what is within my grasp.

When he started laying out the organizational structure that would come to be known as the Toulmin model, British philosopher Stephen Toulmin characterized the argument as a living organism, likening it to some sort of entity comprised of a body animated by internal processes: “It has both a gross, anatomical structure, and a finer as-it-were physiological one.” (Chapter 3, The Uses of Argument, p. 87). He again manifested this organic view of phenomena in the preface to the 2003 edition of his seminal work, where he compared books to children who, having left home, go about their lives and ultimately become their own persons. First published in the UK in 1958, The Uses of Argument was initially envisioned as a reflection on the methods of formal logic, and more specifically the syllogism, which Toulmin considered to have reached an impasse: “Ever since Aristotle, it has been customary, when analysing the micro-structure of arguments, to set them out in a very simple manner: they have been presented three propositions at a time, ‘major premise; minor premise; so, conclusion.’” (p. 89). His intention was to develop a more sophisticated, better adapted analytical pattern in order to accurately determine the validity of arguments. The Uses of Argument was received rather poorly by its intended public, uninterested in this sort of innovation. But, like a teenager, Toulmin’s book joyfully made its way into other neighborhoods, awakening the interest of scholars in rhetoric, argumentation, and informal logic in the United States. Toulmin’s model, referred to variously since then as system, method, layout, schema, or simply Toulmin argument, was thus adopted and given a new thrust.

Thousands of miles away, in Brussels, and unbeknownst to Toulmin at the time, Chaim Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca were having similar insights, which also resulted in a book. Their Traité de l’argumentation, la nouvelle rhétorique was published the same year as Toulmin’s, a coincidence that signaled not only a shared lassitude of the current state of affairs in their respective fields, but that also opened the way to the renewed interest for rhetoric and argumentation that followed, ushering us into what we might call the postmodern stage of argumentation theory. While Perelman’s and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s focus was centered on lifting rhetoric out of the dust it had gathered under cartesian influence, and Toulmin’s on superseding the categorical syllogism or “geometrical model” of logic, both were engaged in exploring new frontiers. Their eagerness for change seems to have been in the air, or Zeitgeist, of the post-war period, when, in several areas of society, the Occident simultaneously challenged the institutions of the past and attempted to formulate new models. In retrospective, Toulmin’s and Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca’s innovative proposals appear as an expression of a larger societal movement, a spontaneous quest for the new that would soon be visible in other areas, notably in the artworld, where artists – paradoxically – gave up visual modes to make conceptual, or “idea art” (Lippard, 1973).

It is impossible, however, to assert whether the publications under consideration were instigated by the spirit of the times. What is certain is that their authors shared a common vision about the limitations of formal logic in ordinary reasoning, and furthermore, were determined to reinvent the path towards good arguments. The immediate fate of their respective books was quite different: while Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s New Rhetoric received immediate recognition, and the authors praise for their influential contribution, Toulmin’s work was largely rejected by those of his own discipline. It took several years before other scholar communities, where argument was important, recognized the impact of The Uses of Argument and incorporated it into their work. Another difference between these books, and not the least, concerns the means used by the authors to convey the results of their research. Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca opted for an in-depth examination of discourse patterns and a thorough description of their configurations, contexts and inner mechanisms. Toulmin created a diagram to represent his concept, a choice that deserves to be looked at in more detail.

Diagrams are basically visual representations of things; they offer a different way of observing and understanding our world. Humans have been using visual representation to convey things since time immemorial, producing drawings, sketches and diagrams that sometimes provide the only glimpse into knowledge that would otherwise be inaccessible. The caves of Altamira, in Spain, are an example, housing parietal drawings that stand in lieu of nonexistent documentation. It has been speculated that these images give an indication of our ancestors’ daily routine: hunting food to survive. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, a human figure diagramed into a circle and a square, is another instance of a visual document laden with non-verbal information that is also not exclusively artistic. Copiously interpreted and commented, Leonardo’s drawing inspires artists and spiritual gurus as well as scientists and content-creators. It might be argued that these two examples are drawings, not diagrams, and therefore of a radically different nature than Toulmin’s model. Yet, for the purposes discussed here, they can be said to function in a similar manner, i.e., as symbolic representations. At its deepest – or highest – level, art is about giving to see more that what meets the eye, not about simply copying the outside world. Toulmin’s diagram doesn’t offer the likeness of a model; it is the model. As such, it offers a generic structure that Toulmin perceives as being able to accommodate any and all arguments.

Diagrams operate as a tool to visually depict and organize complex information. They are used to make data available beyond the boundaries of language. This does not exclude the fact that they sometimes contain or convey questions related to speech or language – and this applies to Toulmin’s model – or are entirely devoted to language. This is the case of the Reed-Kellogg system, a method for diagramming sentences in excruciating detail, introduced in 1877 and served as plat de resistance in grammar classes of the past. Another example is the Venn diagram (1880), conceived by the English logician John Venn to show logical relations between different sets and extended by Charles Pierce some years later. I mention just a few of some well-known diagrams that existed prior to Toulmin’s to establish that Stephen Toulmin did not invent the art of diagramming. He appears to be, however, the first to diagram the structure of arguments.

My purpose here is not to explain the Toulmin model but rather to speculate about what led its author to use it, and to contemplate how it works. It seems nonetheless important to start by giving a brief account of its structure and organization, a task that has been adequately conducted before me with an accuracy I don’t aspire to surpass. I will therefore limit this presentation to a general description and some observations.

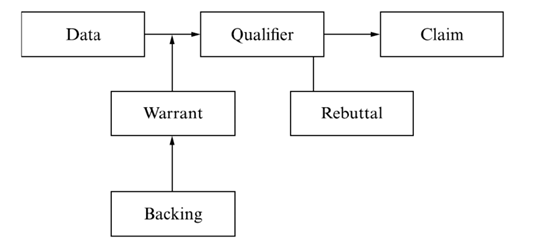

To say it succinctly, the Toulmin model organizes arguments as six-part structures, consisting of: Data, Warrant, Claim, Backing, Rebuttal, and Qualifier. Each of these elements relates to each other in an organic sort of way, as Toulmin would have certainly intended. The diagrams below show the basic layout of the model (Fig, 1).

Figure 1. Basic structure of the Toulmin Model (in “Arguments in Academic Writing”, thesis). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327789354_Arguments_in_Academic_Writing_Linguistic_Analyses_of_Arguments_Constructed_in_Undergraduate_Dissertations_Written_by_Student_Writers_from_Different_Academic_Contexts)

The above graphic suggests the malleability the model. The diagram is not subject specific, and it can be depicted in a variety of manners to satisfy personal visual preferences of the user without modifying the dynamic. Hundreds of examples are available in Internet, proof not only of the continued success of Toulmin’s model but also of its generic nature, which is appropriate to any and all topics subject to argument. Academic programs in various fields teach the Toulmin method as a tool to analyse, evaluate, and construct arguments; using the diagram as a conceptual structure or framework also facilitates invention, an essential element in rhetoric.

It’s better to face it now, we shall never know with certitude why Toulmin chose to diagram argument analysis. But there is room for speculation. When he states the problem ahead (in Chapter 3 of his book, considered by many to be to most important), he acknowledges his options. Setting out to reflect on the matters that preoccupy him, he indicates that he confronts “two rival models, one mathematical, the other jurisprudential”, and wonders: “Is the logical form of a valid argument something quasi geometrical, comparable to the shape of a triangle or the parallelism of two straight lines? Or alternatively, is it something procedural: is a formally valid argument one in proper form, as lawyers would say, rather than one laid out in a tidy and simple geometrical form?” (p. 88). His statement clearly targets the syllogistic approach, and maybe the box and arrow model as well. He intends to supersede the outdated tool with his own model, which he explains in the lines that follow. So, his basic dilemma is how to go about giving this tool a form. Rather than applying a mathematical based solution, he contemplates a procedural one, driven by process rather than by calculation. Maybe he felt a diagram would be practical to show the dynamic taking place in his visualization of the valid argument. It should be noted, however, that according to Toulmin himself, he did not copy the jurisprudence model. When asked about this in an interview (by Michael Boyle), he asserts: “I didn’t base The Uses of Argument on a jurisprudential model. I wrote the book almost entirely, and then at the very end it occurred to me that as a way to add a bit of clarity to the exposition, the comparison with jurisprudence would do no harm.”

Regardless of his intentions – to leave formal logic methods behind – it appears that Toulmin could not truly negotiate a way out. In its simplest format, his new model is made up of three elements: Data, Warrant and Claim, creating an inconveniently reminiscent pattern of the syllogistic triangle he wanted to overcome. Nonetheless, the complete model makes his case: the six elements together introduce a different operative model for looking at the validity of arguments. But if the diagram is to be used as a tool for argumentation, it is obviously still missing some essential elements. Toulmin’s method is about arguments, not about people. Being open and generic, the model is for everyone, one could think, but there is no sight of the “arguer” and the “audience” in his diagram. Introducing the notions of “field dependent” and “field invariant” contribute to situate the discussion in the field of ordinary arguments, allowing for a certain relativism in the process taking place. But still, the human factor is missing. Only by incorporating the participants into the structure would the model be something other than a formula. Yet it’s difficult to conceive how Toulmin could have imbedded the arguer and the audience in his diagram. Parallelly, applying a formula to examine human affairs could never take into consideration all the variables inherent in such matters, leading therefore to misconceptions and misinterpretations. This explains perhaps why Chaim Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, who were conducting a similar investigation, did not consider creating a diagram to illustrate their model. The titles of their books are not misleading, however: The Uses of Argument focuses on arguments, The New Rhetoric on agreement. These are not affirmations, just wild guesses and speculation. Why Toulmin used a diagram and the Belgium based authors did not? We shall never know. In any case, the fact that they opted differently brings to mind the old saying: “Great minds think alike, though fools seldom differ.”

.

By Rose Marie BARRIENTOS, Argumentations Studies, Fall 2019, University of Windsor, Ontario -Canada

.

Rose Marie Barrientos is a Bolvian art historian, lecturer and writer. She completed her studies in France (Sorbonne University), where she co-founded Art & Flux, a research platform on the relationship between art and economy, her field of expertise. She is currently completing a PhD in Argumentation Studies at the University of Windsor, Ontario – Canada.

.

Bibliographical references

Boyle, Michael. “Critical Thinking After the Second World War”, The Electric Agora, November 30, 2015. https://theelectricagora.com/2015/11/30/critical-thinking-after-the-second-world-war/

Lippard, Lucy R. Six Years: the Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972: A Cross-Reference Book of Information on Some Esthetic Boundaries. New York, Praeger, 1973.

Perelman (Ch.) et Olbrechts-Tyteca (L). La nouvelle Rhétorique. Traité de l’Argumentation. Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1958.

Reed, Chris and Rowe, Glenn. “Toulmin Diagrams in Theory & Practice: Theory Neutrality in Argument Representation” Division of Applied Computing, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN Scotland, UK. http://arg-tech.org/people/chris/publications/2005/ossa2005.pdf

Toulmin, Stephen. The Uses of Argument, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1958.

Various authors. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Metaphysics Research Lab – Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.