By Dominique Lancastre

.

« It was not the end. I knew that one day I would return to it, with Dylan beside me. » Dominique Hunter

.

It is not very often you come across a remarkably interesting story like this. I am not particular fond of memoirs as I think that most of the time, they tend to tell the story of the author which can be tiresome.

However, An Ambiguous Grief is totally different; Dominique Hunter is tackling an exceedingly difficult story. She tells us about her son who died at the age of 23 from a drug overdose. It could merely be a banal story of a son that turned bad but not at all.

As the story develops, we discover a huge amount about the author’s son, Dylan. He was born with some deficiencies and as he grew up, he found it extremely difficult to cope with everyday activities that normal kids usually do. The story recounts his struggles, and his fights against the illness until something tragic happens as he uses opiates to relieve the disorders.

Dominique Hunter succeeded in bringing her son back to life through this book and as the reader gets further into the development of this story, compassion arises both for the mother and the son. We know right from the beginning that the son died but we only find out the real cause of death at the end of the book.

In brief, An Ambiguous Grief is a beautiful journey. Through the conversations between mother and son, the reader forgets little by little the son’s demise; the focus shifts to the good moments he shared with his mum during this period. An Ambiguous Grief is a memoir but not a sad one. Dominique Hunter who lives in the USA agreed to answer some of my questions. Here is what she had to say about the book:

.

1. Could you tell us a little about your journey?

.

That is for the reader to discover in the book since that is what it is all about! This is the poignant portrayal of the death of my son at twenty-three, our conversation over time, and our journey towards understanding what happened to him with as little sentimentality as possible, but with as much humour and honesty as possible.

.

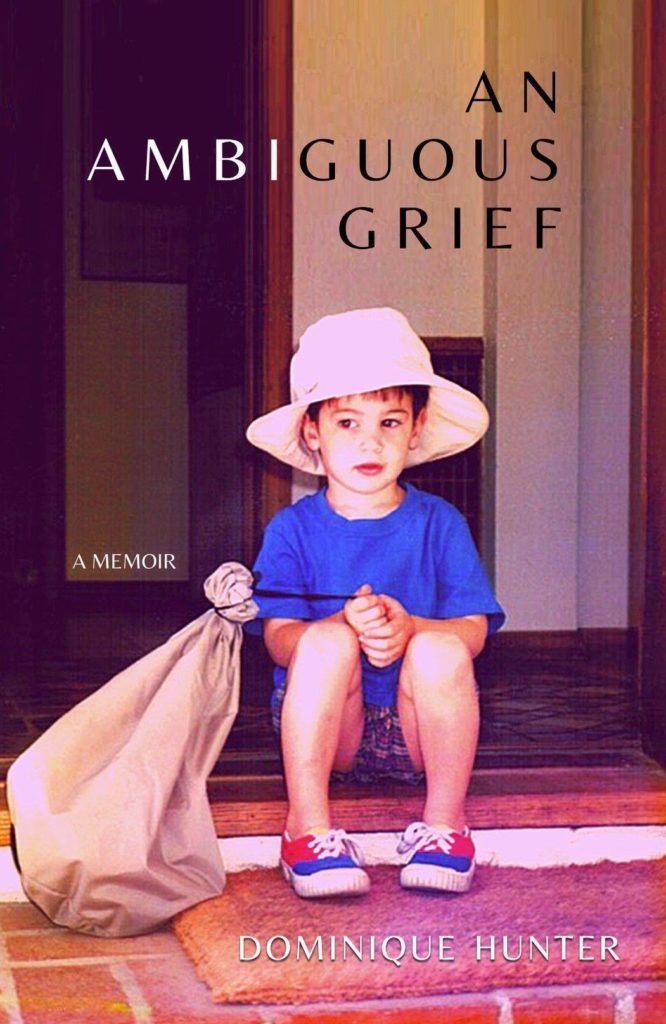

2. About the cover, does it feature your son? Tell us about this choice.

.

Yes, it is my son at four years of age. I took that picture myself, and I suggested it to my editor as a book cover because I believe it symbolizes our story perfectly. The large burlap sack that Dylan is holding is still closed. It contains all that he would have to deal with at the onset of puberty – his ADHD, his anxieties, his dyslexia, his OCD and finally his intake of opiates to help quieten his mind. Our quest was to reach an understanding together: why it all spilled out of the sack, and why we could not keep it in.

.

3. Why did you write this book?

.

It is a testimony of a mother and her young son’s journey into the monstrous and yet all too human world of mental disorders.

.

4. It is not a format you often see because it is a conversation between you and a deceased person? Why this choice?

.

Our conversation beyond time reflects all the conversations we had when he was here. It recalls all that, really. It was important for me to keep his voice alive, and to let the reader hear his own words.

.

5. There are digressions in the book with passages set in Italy. What was the reason for this?

.

I wanted to give Dylan a second chance at life: a life in a time and place where such disorders would have been easier to deal with. Dylan had a ferociously artistic mind. He loved music and he loved stories. Renaissance Italy was the perfect spot for him – a time of renewal and a time of immense creativity: a time when arts were at the very centre of political and social power. I decided to apprentice him to the Amati family, the first and most prestigious family of violin makers.

.

6. What message did you want to convey through this story, and do you think it might help other people?

.

I wanted to show how difficult and challenging it is to raise a boy with mental issues and how these disorders lead inevitably to the need to self-medicate. Parents should always be aware of that without second guessing themselves. I also wanted to show them that they should never feel guilty or responsible for these disorders.

.

7. Psychologically what did you draw from this experiment?

.

I figured out how and why the disorders spilled out of the sack.

.

8. What was your state of mind when you typed the last sentence and knew it was over?

.

It was not the end. I knew that one day I would return to it, with Dylan beside me.

I resolved never to take any money from the sales of An Ambiguous Grief.

That would just be too obscene. The entire proceeds have been lodged in the BBRF account – the Brain and Behaviour Research Foundation in New York City.

Dylan’s brother, Adrien, who is now 36 years old, has raised money for them in recent years (more than $27,000 to date) by competing in American triathlons.

.

.

Dominique Hunter was born and raised in the Languedoc, in the south of France. In 1979, she moved to Berkeley, California. She married an American and had two sons. She loves animals, American Jazz and the cello. She resides in Oakland with her husband and Babette, her sassy Aussie.

An Ambiguous Grief is published by Atmosphere Press in the USA and is available throughout the USA and abroad.

.

EXCERPT

.

In bed at night, as sleep eludes me, I often have a song circling in my head, one of the French yeah!yeah! songs from my youth that seems to come out of nowhere. It must have tucked itself so deeply into my psyche that it only pops out in the vacuum left by my insomnia.

It wouldn’t be unpleasant if the song wasn’t running on a loop and if I was able to stop it. But no matter what I do, it keeps going. I try to pry my mind off it by focusing on something else, something tangible and dear to me, like what new plants I will get in the spring for the garden or our trip to France in the summer – shall it be in the Dordogne or Provence? Shall we skip Paris? I think about the book I am reading or about the meal I will cook on Sunday for your brother who comes every Sunday to be with us since you left.

I think about everything I can think of, but the damn song remains in the background like a soundtrack to my thoughts, and it drives me crazy.

I think of you, then. I think of how your own obsessive thoughts seared your mind with the fear that Glenn or I could die, that one of us had cancer and was hiding it, and the anxiety that followed was so powerful you had to perform your rituals. At home by closing and opening doors, taking a few steps this way and that, going outside to tap-tap-tap on the wall with two knuckles, rhythmically and with a pattern: Three knocks and stop, three knocks and stop, then five knocks and stop. Again. Three knocks and stop, three knocks and stop, then five knocks and stop. If ever a third knuckle touched the wall, you had to start all over. Three knocks and stop, three knocks and stop, and then five knocks. At school by tapping quietly under your desk with the rubber end of a pencil – tap-tap-tap, tap-tap-tap, tap-tap-tap.

I see now how absolutely mad it was, like being unable to turn off a faucet all the way, and being forever condemned to hear the drip, drip, drip of water inside the pipes of your brain.

No wonder you needed drugs. No wonder you went out and found them! Who could blame you?

You did! Glenn did! Adrian did! You all did!

Of course, we did. You were our son! You were his brother! It was so very raw and personal and complicated, don’t you see? How could we allow ourselves to agree to your choice of relief, which was a complete shutdown of your mind? It was maddening, and there were so little choices. Cigarettes? I fought Glenn to let you smoke…

Outside the house, off our property, out on the street!

…thinking it was a minor health scare compared to the alternative. And yes, outside on the street. Of course, outside on the street! Not that it helped any.

It helped me stop chewing my fingernails for a while, but that wasn’t enough. Nothing was enough. Not even the weed Glenn gave me.

You called it hippie weed because it was so mild. Meanwhile, what you smoked didn’t just get you high, it got you wasted.

That was the idea, Mom.

And you went right back to chewing your fingernails, down to the quick.

You called me chewy! Chewy or stumpy!

You called me wrinkly!

Only fair.

Let’s high five that!

.

Related Links

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Ambiguous-Grief-Dominique-Hunter/dp/1649218818/

Indiebound: https://www.indiebound.org/book/9781649218810

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/54025527-an-ambiguous-grief

Brain and Behavior Research Foundation: https://www.bbrfoundation.org

.

Book Review by Dominique Lancastre (CEO Pluton-Magazine)

Pluton-Magazine/ Paris 16eme/ 2021