.

By Dominique LANCASTRE

.

House of Fossils is a remarkably interesting and challenging novel. The book begins with the author finding herself in a remote town by the sea in Nova Scotia. She was supposed to spend one night there as the strong winds had brought her. She meets Saul who kindly rented her a strange house for the night; it was impossible to find anything else in the town. Saul is somewhat weird . He used to be a fisherman but no longer enjoyed his work; he now has a different conception of the relationship between the sea and the fishermen. Then a strange and shy girl named Mattie appears… but the reader soon understands what Marilène Phipps is referring to.

This is the first chapter of the book but as the story develops the reader notices that every single chapter is different. One might say that as the chapters are different perhaps they are unrelated and it is not a novel but a short story. However, this is not the case at all. Being different does not mean that there is no consistency in the story. As a matter of fact, it is impossible to pick any chapter and read it that way. It would not make any sense.

Marilene Phipps is telling the story of Haiti through her own eyes and also through the eyes of different people. There are many historical references about Haiti and yet House of Fossils is not a historical book. The references are there to help the reader who may or may not know about Haïti.

Furthermore, we must not forget that the author herself is Haitian. She is describing Haïti from afar putting together her best memories of the country which she had left. In one chapter, she tells us about Europa her sister; as a matter of fact, there is always a part of a book that a reader likes best and I think this is the section. It presents a great image of what the author wants to convey to us. What makes House of Fossils an interesting book to read is the ability of Marilène Phipps to distill lots of information in every chapter. The reader gathers this important information and puts it together; by the time you finish the book, the purpose of House of Fossils is all clear. House of Fossils can be possibly summed up in one sentence: I may be white (on the outside) but I am truly a black Haïtian inside and I can prove it…

Marilène Phipps kindly accepted to answer a few questions about House of Fossils.

.

.

1. Why have you written this book using this structure—All the chapters are different?

.

I believe that a work of art comes through us rather than from us. If one allows the mind to float or empty itself, letting divinity enter to inspire us, then the work—or the guide to the work, the soul of the work—will eventually present itself in the mind to tell you what it wants, how it wants it (but never why).

Some light about my approach can be found perhaps in my previous book, “Unseen Worlds: Adventures at the Crossroads of Vodou Spirits and Latter-day Saints—a memoir. I wrote: “A country’s history can be studied through the geological stratification of its layers. Human lives are in layers as well and can be examined like geology; the stories we tell of ourselves reveal the ways in which we are stratified; we are a kind of earth, dust similar to that which we are meant to become and return to; we are ancient cities that can be uncovered by archeological digs, showing how new rooms and space in us are continually added onto the old.”

It could be said that the way I have structured House of Fossils shows this stratification happened in my being and life. Our lives are built in slices of time, and we slowly become a compilation of layers. I was inspired to reveal slices of my life within the whole, even if within only ten years as presented in this book.

I am interested in the ways people react to life situations. Even if one experience turns out to be a transformative one, its place in a sequence of events or moments is what holds meaning, what happened before and what ensued after.

One could say that all my books are one book—each one tells a story by telling several—each one is an act in an ongoing, unfolding play. No single event exists in a vacuum. No human life can be told from a single experience.

.

2. You seem to suffer from the fact of being a mulatto and Haitian. Is this something you wanted to sort out in this book?

.

This is not something I wanted to sort out. But I did think that related issues to my identity as a mulatto needed to be addressed.

A Haitian academic friend of mine who had a prestigious career as a sociologist in the US said about the book, “these things needed to be said…” Going back several decades of Haitian history, I find that every generation of men in my family have been involved in coups d’états or some attempt to overthrow unsatisfactory governments. My cousin and godfather died at 24 in 1964 with a group of young mulatto rebels who tried to rid their countrymen of the Duvalier dictatorship.

Perhaps in my own way, as a writer, I have joined the revolutionaries in my ancestry. My gift and potential power are with the written word. Writers are historians of the personal, social, religious and political events of the world and of their world. Writers are the memoirists of the human experience and journey. That is their mission and duty, which is ultimately a moral one. Our life stories have universal lessons and healing power; telling them benefits everyone. Truth, however brutal, is honorable. Abuse thrives in secrecy. Writers must stand for and bring attention to the voiceless and the invisible among us; they are agents for the rise of our social conscience in a fight to bring about the dignity, health and happiness for all beings.

Being a Haitian mulatto is not a simple issue of skin color.

Being a mulatto in Haiti generally alludes to a privileged situation—personal, familial, economic and socio-cultural. But being a Haitian mulatto refers to an old, long, painful colonial history of slavery involving white masters against black Africans.

Being a Haitian mulatto means being part of a history that speaks of 298 years of slavery. Slave rebellions against the white masters started in 1790 and ended successfully in independence in 1804. However, the disastrous personal, social, and economic effects of colonization have been difficult to overcome wherever it has occurred in the world, whether inflicted by the French, Spanish, English or the Germans. Haiti has been no exception in this struggle.

Back in 1804, no country in the world would concede Haiti’s independence. The interests of slave-based colonial empires were threatened by the example set by slaves in Haiti. The United States (with its 28 million blacks in America), along with the European powers challenged Haiti’s sovereignty and they worked together to suffocate the new country. To give a few examples: there was the Franco-American embargo of 1806 when all trade was shut down; then France imposed a 92 million gold Francs indemnity—10 times France’s own yearly budget at the time—for its losses in the slave trade and the exploitation of Haiti’s land resources; and then racism was brought back to the island with the 15-year US occupation of Haiti started in 1915.

A quick overview of politics and government during the first 200 years of Haitian independence illustrates the difficulties the new nation experienced. Between 1804 and 2004, Haiti has had 44 presidents. “Of these forty-four presidents, one retired, one stepped-down, and five died in office: a derisory total of seven peaceful, orderly transitions of power… Of the 37 fellows left, one was ousted, nine were forced to resign, seven were overthrown, thirteen fled abroad, Henri Christophe committed suicide, one was assassinated, one was executed, Tancrede Auguste was poisoned, Oreste Zamor was murdered in jail, Vilbrun Guillaume Sam was lynched, impaled and dismembered, and Cincinnatus Leconte was blown up by a bomb.” (Unseen Worlds; chapter 2).

Haitians in 2021 are still suffering from the aftermath of colonization as evidenced by enduring economic distress, social division of class and color, and continued, violent political instability.

It is important to understand the dictates and enduring consequences of a racist colonial system that caused such internalized self-hatred as to inspire the abused person to admire, envy, and imitate the abuser. Haiti is a country still inhabited by a population with a complex color scheme and complicated attitudes about it.

Haitians in positions of power have worked hard to make Haiti inhabitable. There has been a mass exodus of both mulatto and poor black populations primarily to the US and to Canada in the past 30/40 years as a result of dictatorships, governments’ incompetence and greed and the ensuing, continuing social misery and unrest. The government incompetence and resulting exodus itself are still residues of the effect of Spanish and French colonization in Haiti.

By and large, Haitians who have now emigrated abroad, second and third generations getting educated and thriving, have overcome the black and white complex. But in Haiti, the situation is unchanged.

So, no. I don’t suffer from being a mulatto or a Haitian. Being both a Haitian and a mulatto has been a privilege. But in my view, privileges come with human obligations and moral burdens. I believe that there is divine meaning and intention for us to be born in a particular place and country. It is for us to understand it and apply ourselves to act on it.

Still, as elegant, generous family members, passionate for their island and refined as the old mulatto class in Haiti may have been, it must be admitted that the ways in which they have used their political and monetary power, and their intellectual advantages, towards the country and their countrymen suffering in endemic poverty, have been and remain a poor show on the whole.

“The US did not give a cent in gifts to Haiti” Haitian historian Roger Gaillard explained many years later in an interview about the US occupation of Haiti with Jean-Roland Antoine, “…its occupying forces gave us an elbow shove that said, ‘get up from that desk, I am going to manage your country for you because you are incapable of it…’ Whose fault is it? It is our own fault—blacks and mulattoes—I am not ashamed to be Haitian, but I am sad to be Haitian… Back in 1915, we had no army, no administration, no roads, no hospitals. We had been incapable of performing on our own the tasks of a nation… And these were neither revolutionary nor were they socialist tasks… the occupying forces substituted themselves in places of our dominant class to perform the tasks incumbent on us—the educated, dominant class—but that we just could not fulfill.” (Unseen Worlds, page 37).

.

3. Why this title: House of Fossils.

.

The title was inspired by the first story in chapter one of the book, “The Ghost of the Mary Celeste.” It was originally called “House of Fossils,” for obvious reasons if one reads the book.

I thought this title would be appropriate for the book which is a form of protest against the fossilization in people’s feelings, cultural attitudes and behaviors, refusing to examine themselves and to evolve.

For this reason, I see my book as being about betrayal—a denunciation of it and protest against it. Betrayal in families, where the love and support due are replaced by enduring jealousies, power games, and efforts to spite one another; betrayal in societies where racism, marginalization and abuse win over unity, compassion, and plain human decency about the way we treat each other; political betrayal where governments and the dominant class are corrupt and use their privileged positions and power for personal profit, amassing wealth at all cost even if it means torture, murder, assassination, theft, rape and the loss of their soul.

.

4. What do you think might shock, or not, a Haitian reading this story?

.

No. Haitian should not be shocked by recognizing the truth about the moral, spiritual or political indecency happening in the country, to its people, or to themselves. If they are shocked or offended, it should be a vivid call to examine their lives, how they “love their neighbor,” and to work individually and collectively towards making changes.

Fourteen academics and/or writers of note have written comments about the book (all of which are reprinted in the book). Four of these are Caribbean people whose islands were under colonial rule: Three from Haiti and one from Jamaica (Geoffrey Philp). Mentioned alphabetically:

—Patrick Bellegarde-Smith: “This novel is transformative… Phipps is a major voice… and she opens painful doors for the reader, and for this, I am grateful.”

—MJ Fièvre: “This is an important book—one that will move you and stir serious discussion with others and, most importantly, with yourself.”

—Geoffrey Philp: “House of Fossils expands our understanding of… the historical implications of colonialism in the Americas.”

—Katia D. Ulysse: “… This is required reading for anyone seeking to commune with humankind on a level that transcends language, country of birth, or even the physical world…”

.

5. It is not a biographical book, but you put lots of your parents in it? Why?

.

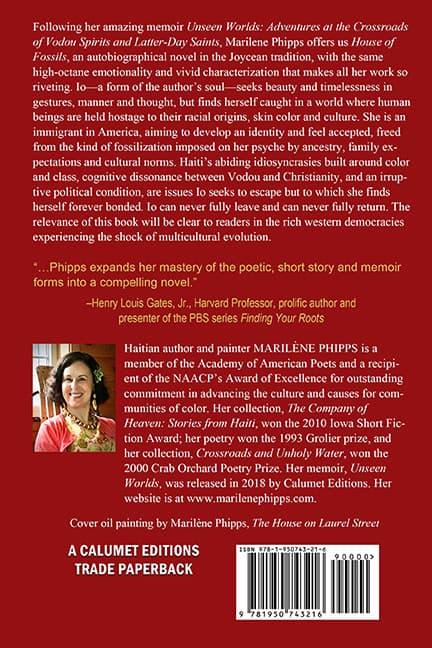

On the back cover of the book, the editors have described the book as “an autobiographical novel in the Joycean tradition.”

This reference to James Joyce’s writing in a way says it all and should suffice. But I might add that we write best about what we know. I started my writing career as a poet, which implies a very immediate, intimate and personal kind of gaze at oneself and the world around one.

A writer whose name I forgot once said that “all fiction is autobiographical.” This may be an extreme point of view, but it is undoubtedly true that our fiction is stimulated and enriched by personal experience or that of others close to us or those we meet. Family is generally always part of our human experience in one form or another. So, family members mentioned in a novel need not be real to feel real. For example, Io is the heroine in House of Fossils, and whose sister, Europa, is a vivid character, when, in real life I never had a sister.

But I do use elements of my family’s history and ancestry in one chapter. One often hears that people are truly dead when no one speaks of them or remembers them any longer. We all have greater and lesser aspects in our being; so did my family; so do I. But I love all of them, I feel pride in them, gratitude for them, and, for better or for worse, this book is the expression of my “Remembrance of Things Past.” (Marcel Proust: “À la Recherche du Temps Perdu”).

.

6. The story of the French guy you meet on the plane coming back to Haiti. Is it a true story?

.

Absolutely! I did sit next to such a man once, on a plane going home.

.

7 You are bilingual have you got the intention to continue writing in English or will you eventually switch to French from time to time?

.

My mother came from France and my parents were married in France. I spent my adolescence in France where I did my schooling in Paris lycées/schools and a couple of years at a boarding-school in Saint Germain-en-Laye. My writing skills were my strength throughout my school years and rose my grade average so much as to allow me to graduate with honors from the French Baccalauréat exams. But I have spent my adult life in America, speaking and writing in English. I attended two American universities, studying at first for a Bachelor’s degree in anthropology at Berkeley, California, and then for a Masters in Fine Arts at Penn, in Philadelphia.

My mother died last February 2020 in Haiti. I promised to her on her deathbed that I would write about her life. Since then, I have only read books in French. It has been a rich experience so far, reading and writing in French—reconnecting with this deep French-speaking part of me—my first language, the words through which I learnt to feel and articulate the physical world.

I am also seriously considering the translation of House of Fossils into French and have been looking for a translator. In the meantime, I have begun the translation myself. That too is a rich experience. It is as if I am discovering the book I wrote.

.

.

About the author

.

MARILÈNE PHIPPS was born and grew up in Haiti. She is a member of the Academy of American Poets and a recipient of the NAACP’s Award of Excellence for outstanding commitment in advancing the culture and causes for communities of color. Phipps held fellowships at the Guggenheim Foundation, Harvard’s Bunting Institute, the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for Afro-American Research, and the Center for the Study of World Religions. Her collection, The Company of Heaven: Stories from Haiti, won the 2010 Iowa Short fiction Award. Her poetry won the 1993 Grolier prize, and her collection, Crossroads and Unholy Water, won the 2000 Crab Orchard Poetry Prize. Her memoir, Unseen Worlds, was released in 2018; it was shortlisted for the Next Generation Indie Book Awards. Her new novel, House of Fossils, was released in March 2020; it was shortlisted for the International Book Awards 2020, the National Indie Excellence Award 2020, and was voted by Kirkus Reviews as The Best Books 2020. She has contributed to American anthologies and collections such as The Best American Short Stories; Haiti Noir: The Classics; The Beacon Best; New Caribbean Poetry (Carcanet Press England); Others Will Enter the Gates; Ploughshares; River Styx; Callaloo; Dove Song; and Harvard Divinity Bulletin. She edited Jack Kerouac Collected Poems for The Library of America.

Find House of Fossils on Amazon at http://smarturl.it/FOStg.

Her website is at www.marilenephipps.com.

Find all her books at the appropriate university presses or on Amazon at https://www.amazon.com/Maril%25C3%25A8ne-Phipps/e/B07GDVNY5H%3Fref=dbs_a_mng_rwt_scns_share