By Dominique LANCASTRE

.

.

Dangerous Freedom tells the story of Elizabeth Dido Belle, known historically as Dido Belle. She was born into slavery in 1761 in Pensacola, Florida, to an enslaved African woman, known as Maria Belle. Her father was 24-year-old Sir John Lindsay, the nephew of Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of England. Lindsay returned to London in 1765 with his young daughter, Dido Belle, and Maria Belle. He arranges for his daughter to live with his uncle and aunt, Lord and Lady Mansfield.

Being in the navy and always at sea, John Lindsay realized it was difficult for Maria Belle to protect her daughter. He pointed out that Dido could be snatched very quickly, as is clear in this exchange between Lady Mansfield and John Lindsay.

“ Your uncle will do anything for the family. You’re his sister’s son. He’ll be on the bench all day . But I’ll have to become a kind mother to the girl. I won’t know how…

‘ You can’t be her mother. She’s got a mother. You’ll be her guardian. I know you’ll be kind. You know the streets of this city are treacherous with catchers, only too eager to slap irons on her, throw her onto a ship bound for Kingston, Bridgetown, or elsewhere. My daughter, just a mite, will be snatched. The mixed race ones are the most desired ‘ ”

Later in the novel, Elizabeth marries John d’Avinière, a Frenchman who works as a gentleman’s steward. They have three children: Charles and Johnny, twin boys and later another boy, William Thomas (Billy). Charles is darker than Johnny despite the fact they were twin brothers.

As the story develops, we understand that Elizabeth, as an adult, and now married with her children, living in Pimlico, London, spends a lot of time at her desk writing her own story. Through her writing she recalls her life, her childhood with her mother and young woman-hood as Dido at Caen wood, the Mansfield house.

At the beginning of the novel, we further learn that she has a cough which causes alarm and which she does not want her children to notice. Her main concern is what is going to happen to them when she has gone.

Johnny’s attentions always affected her greater intensity because of his soft intimacies, which appealed to her secret longing for a daughter, though she knew that a girl child might not survive as well as the boys with their father when she had gone.

When Elizabeth learns that a strange man is following her two boys she cannot but think of what her mother had told her as a young girl; she was a black and a slave, no matter how much of John Lindsay’s blood was running in her veins. The boys faced racism at school, but it only became apparent to Elizabeth and John, her husband, when she heard of the man’s pointed comment about Charles, that her boys could fetch a good price, as both boys were returning from school one day. The idea of having their boys captured and sold because they were black and mixed race brought back memories of her own fear of being captured when she was a child.

At this point in the novel, Elizabeth was at that time terribly ill, and it was becoming difficult to hide the coughing and bleeding, particularly from Lydia, the housemaid. Knowing that she was dying, Elizabeth was still focused on putting her memories together in writing.

When the weaker twin, Johnny, fell ill with diphtheria, this brought back memories from her own childhood with Beth, the other great-niece of Lord Mansfield with whom she grew up. She also remembered her mother telling her that she, Maria, could never be married to her father. He had married another woman called Mary Milner, and yet he was still visiting Elizabeth’s mother and sharing her bed. She was introduced to her stepmother, though she could not become her mother because of her skin colour.

“You know I can’t make her my wife. I cannot make her a lady. My knighthood, besides. It’s impossible. Their skin speaks volumes before they even enter a room or dare to speak in their lilting sentences It is unfortunate. I do confess to have been smitten for the first time by the beauty of a woman”

All these memories were racing through Elizabeth’s mind as her condition worsened. Her own concern was how to protect her sons from the ill-doings of society when she was gone. The couple realized how important it was to protect their sons not only from being snatched away to be sold as slaves, but also from all kinds of misfortunes and illnesses.

Drifting through memories, Elizabeth realized that she could never be free. She had called Lord Mansfield, Master, but never uncle. Her own story made her understand how difficult it might be for her sons to survive in England after her death.

When later, Beth informs Elizabeth that she was going to be visiting her with her own children, Elizabeth could not help but remember how Beth treated her as a child. These memories brought back the James Sommersett affair of a slave being recaptured and sent back to America, which Lord Mansfield was judging as the Chief Justice of England. Dido’s mother had said many times that capture could well happen to her.

At this point in the novel, the author’s intention becomes clear. Lawrence Scott wants to give a voice to Elizabeth and to those mixed-race slaves, brought to England as free men and women though they still belonged to their masters; being captured and sent back to the West Indies or to America was still a very real possibility.

When her mother returns to Pensacola, leaving Dido without the only person she had had a deep connection, even if they were not living in the same place, made Dido an incredibly sad girl from the beginning; she also had to cope with racism and the fear of being captured.

As the novel develops further, Beth visits Elizabeth with her children. Being ill and having to cope with Beth, who had not changed since they had last met as young women, was stressful for Elizabeth. Beth had always been in competition with Dido, and even after years apart, she still took every opportunity to remind her of the colour of her skin and what she was before: a slave.

This is a turning point in the novel. This is one of the best parts of the book, and it shows the genius of the author, as he handles the results of Beth’s visit and the memories, which the visit stimulates for Elizabeth.

As Elizabeth’s health deteriorates, it becomes imperative for her to try to get in contact with her mother, despite the many years that had passed. This yearning for her mother is central to the emotional pull of the novel.

However, this is where Pluton-Magazine leaves the reader to find out the outcome of the story for themselves. Do enjoy this outstanding piece of literature: Dangerous Freedom is a book, which deserves to be read by all.

.

Dangerous Freedom : Lawrence Scott interview

.

.

Why write about Elizabeth Dido Belle?

.

She is a figure in the 18th century without a voice. She was a mixed-race girl/woman from the wider Caribbean of the time, Pensacola in Florida. This story intrigued me once I began to learn more of Dido’s life. She is framed famously in David Martin’s double portrait of herself and Elizabeth Murray, Beth of the novel, as an exotic, wearing the well-known features of the enslaved from 18th century black portraiture, exoticized and sexualized. I wished to free her from that frame and give her a whole life of her own.

.

Did the title of the book come in a flash of lightning to you or did you think about it? Sometimes authors change the title.

.

The novel was first of all written as a first person narrative, entitled “Elizabeth d’ Aviniere’s Testament”. It was then changed to “Capture” and then again to “Captured” once that theme and plot came to the fore in the story. In the end, my editor at Papillote Press, Polly Pattullo, came up with Dangerous Freedom which encapsulated both the negative and the positive aspects of the story. So called freedoms were dangerous in 18th century because they could be reversed. Also, the title points to the danger freedom meant to the rich planters if their enslaved were to be freed and they were to lose their property and hence their fortunes. There are a number of ironies in the title.

.

Dangerous Freedom is a remarkably interesting book how long did it take you to write this story?

.

My interest in the story began very early – as early as 1995 when Dido appeared in a poem of mine called “English Heritage.” The poem is set at Kenwood House with its park, which is the fictional Caen Wood of the novel, an early spelling of the name of the house and park. I have notebooks going as far back as 2013/ 14 where Dido and Elizabeth both appear, their voices beginning to be created. Once my previous novel, Light Falling on Bamboo was published in 2012,I began to research this novel in a more focused way. The research and the writing was completed in 2019. But of course there were interruptions: a collection of stories, Leaving by Plane Swimming Back Underwater was published in 2015, and then the 25th anniversary publication of Witchbroom, my first novel, came out in 2017 and the launching of my literary archive, 2018. This is being housed in The West Indiana Collection at the University of the West Indies in St Augustine, Trinidad & Tobago. I usually take four to five years on a book.

.

As the story develops it appears to the reader that the author has developed a kind of special connection with Elizabeth’s view. Am I right?

.

I have of course tried to create Elizabeth as an independent character with her own voice, but, yes, she does in some ways express my views on the politics and horror of 18th century African enslavement. I bring my own emotional experiences, though completely different, to empathize and learn how to inhabit her, so as to discover her and to imagine her for readers. I try to follow what Toni Morrison says in her essay, “The Site of Memory” about the work of the writer: “That the ability of the writer to imagine what is not the self, to familiarize the strange and to mystify the familiar is the test of their power.”

.

Apart from the fact that nobody can be deported to be enslaved Dangerous Freedom points out some interesting topics that are true even today. Do you get angry with that, and why?

.

Yes, while the book was being written a long time before contemporary events, for example, the Windrush scandal in the UK, and the Black Lives Matter demonstrations following upon the George Floyd horror, and many others at present and in the past in the US, the book does, in its own way, resonate with these contemporary events. I have said on occasions that I wished the novel to add to our understanding of a pain that remains just below the surface of contemporary life, which is due, in large measure, to racism and to the unacknowledged events of past colonial history. In my work, I return to “the site of memory” as Toni Morrison calls it, to recreate, to repair and to heal.

.

If you had to choose one particular excerpt from Dangerous Freedom, which one would you pick?

.

I think that the first few pages of Chapter 12 express some of the conflicted politics of the novel in regard to Lord Mansfield and the trials that he had to judge. That is one important side of the novel. I think that many of the passages which dramatize Dido’s early relationship with her mother and then of course later her mother’s letters, point to what I think is the central emotional pull of the novel. This is a child’s and then a woman’s yearning for her lost mother – a mother for her daughter- as Elizabeth is obsessed with the safety of her own children; herself traumatized by her own childhood threat of capture.

.

Dangerous Freedom gives a voice to people who could not have a voice at the time. Is that what you aimed for?

.

Yes, I think I have explained that above, that is my intention, to give voice to those whose voices have been silenced or erased altogether.

.

You were born in Trinidad but live in London. Do you feel, or have you ever felt, uprooted?

.

I don’t feel uprooted. It was my choice to come to England to enter a Benedictine monastery in 1963 at nineteen. Once I realized that that was not a life for me after four and a half years later, I had already settled into the idea of staying in England with the advantages it gave me for education; I could not see myself, at that moment, returning to Trinidad. I then had my university education and trained as a teacher. When I did return to Trinidad with my partner Jenny Green many years later, in 1977, to teach and to live in Trinidad and stay there for three years, I began to experience a conflict between the two places. I decided to devote myself to writing at that stage, having rediscovered Trinidad, inspired by its landscape, history and culture through writers and artists and my own reading. I also renewed the memory of my childhood. I made important writerly friendships, for example, with Earl Lovelace, who was certainly an important inspiration, as was Derek Walcott. The conflict between places remains and is in fact a creative conflict. I now travel frequently between the two places; so, no, not uprooted but conflicted. On the whole, I think I have now, in my 78th year, decided that London is home as well as Port of Spain. I stay longer in London, which I cannot imagine leaving. Of course, I am now stranded in London and deprived of Port of Spain, because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Conflicted yes, but I think a greater balance has been established. My partner Jenny is British, so that is also an important reason that we are here in London, though she has made a close relationship over many years with Trinidad, and with our many friends there. I remain, in my heart and imagination, Trinidadian, but with a love of London, the place of my main teaching experience and where my love of the English landscape, as expressed in so much of its poetry, is an inspiration for me.

.

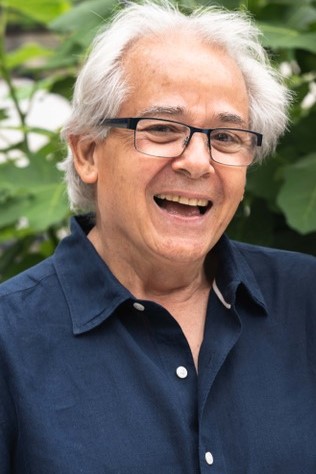

About the author

LAWRENCE SCOTT is a prize-winning novelist from Trinidad & Tobago. His most recent novel is Dangerous Freedom (2021) He was awarded a Lifetime Literary award in 2012 by the National Library of Trinidad & Tobago for his significant contribution to the literature of Trinidad and Tobago. He was elected as a Fellow of The Royal Society of literature in 2019. His second novel Aelred’s Sin (1998) was awarded a Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, Best Book in Canada and the Caribbean, (1999). His first novel Witchbroom, aBBC “Book At Bedtime,” (1993) had its 25th anniversary of publication with a new edition, (1992-2017). It was translated into French, Balai de Sorcière (2020). His other novels are: Light Falling on Bamboo (2012) and Night Calypso (2004), Calypso de Nuit (2005). His short stories have featured on BBC Radio 4. His collections of short stories are Leaving by Plane Swimming Back Underwater (2015) and Ballad for the New World, (1994) which includes The House of Funerals, awarded the Tom-Gallon Award by The Society of Authors (1986). He is the editor of Golconda Our Voices Our Lives, (2009), a collection of stories, poems and archival photographs collected through a Public History project conducted on the Golconda sugarcane estate in Trinidad. (UTT Press 2009)His poems are published in a number of journals and anthologies. His website is: www.lawrencescott.co.uk

.

.

.

Dominique LANCASTRE (Ceo Pluton–Magazine)

Pluton-Magazine/ Paris 16/2021