.

By Rose Marie BARRIENTOS

.

Archeological evidence in the shape of animals painted in a cave suggests that seeing the world was never enough, we also felt compelled to represent it. Our desire to capture our environment through the image has found multiple expressions throughout history; many means have been employed to that end. Images allow us to reinstate reality, to re-present it as it appears to our eyes at a given moment, or to show it as we wish it were. The captured image thus appears as a tool for understanding, interpreting, and translating or conveying reality, which explains perhaps that it awakens the interest of both the aesthetic and the political thought. The complexity of this double anchoring might have been exacerbated with the invention of photography, a more immediate means of apprehending the world, which also renders its images more realistic. A latecomer among our reality-capturing devices, photography has had the greatest success, nonetheless. With the advent of the smartphone camera, taking pictures is a daily ritual whose long-term impact in our perception of the world remains to be assessed. Conceived in a laboratory after years of research, photography was born in the first quarter of the nineteenth century[1], child of an inventor and an artist who, haunted by the prowess of the camera obscura, dabbled in physics and chemistry until they achieved an update. A cohort of enthusiasts quickly developed improvements on the initial idea and by 1888 cameras could be purchased by the general public. In simple terms, a photographic image is the result of a chemical process that when associated to the properties of light – a principle central to physics – transforms a latent image into a visible one. During the photographic processing or development, the image is rendered insensitive to light, becoming therefore a permanent print. Images of the world could thus be immortalized. In his project L’autre rive, Emeric Lhuisset obliterates this principle by modifying the chemical process so that instead of remaining fixed, the image disappears progressively when exposed to the light. There is a reason for this: with the image gone, other realities come alive.

Emeric Lhuisset is not a photographer strictu senso, although much of his work relies on this medium. His approach is like that of a “historian, an analyst, an archivist”, says an art critic of the artist (Dagen, Arte TV); the latter claims that what he does is “retranscribe geopolitical analysis into visual forms.”[2] This characterization opens a broad transdisciplinary field and formulates a common ground for the aesthetic and the political, failing however to address how one might overcome their perceived interpretative incompatibility (Azoulay, 2010). The artist’s formulation implies that art and geopolitics can be made to coexist and can in fact be articulated as one through visual and textual language. Can there be a cordial agreement between these different categories and methodologies? And if so, will this result in achieving what Azoulay calls for in her text: Getting Rid of the Distinction between the Aesthetic and the Political? A couple of Lhuisset’s works will allow me to contemplate these issues. While of different nature and dissimilar topics, the two images I selected bring to light a mechanism that appears with consistency in the artist’s work, allowing him to overcome the (hypothetical) chasm between the aesthetic and the political. It’s a visual strategy that takes different forms but appears to allow him to dodge an either/or approach. In the works examined we shall see he favors neither while giving visibility to both.

I met Emeric in Paris in the late 2000s, when he was running Mercenary International Corporation (MIC), an artist company[3] specialized in private security services. These were staged through performance with a small team he had gathered for the venture. MIC drew its concept from the mercenary mystique and from palpable fears that had been building up for several years in France (motivated notably by terrorist attacks and urban riots) as the population became aware of the government’s failure to maintain civil peace and ensure their protection. MIC offered a variety of services and guaranteed failproof security, albeit imaginary. I decided at once that fictional protection was better than none and engaged their services. The MIC team arrived at my residence in proper attire and, after an informative session, proceeded to install my “private bodyguard” (Figure 1). It was a life-sized silhouette of an armed soldier, a black paper cut-out unfolded and pasted in the entrance hall. The performance ended with a mercenary story told by the artist in campfire style to an entranced audience I had gathered for the occasion. Once everyone was gone and I found myself alone with my purchased “soldier,” I must admit I felt more troubled than protected. The atmosphere was tense those days. As France faced Islamist radicalization, the fears expressed by civil society were becoming more and more justified. Real soldiers were sent out to patrol the streets. More than once I stumbled upon a peloton when turning a corner and found myself reminded of my installation, forced to come to terms with its prosaic nature. While the “soldier” never left its place, it did not make me feel safe; on the contrary, the shadow lurking in the foyer startled me at night. Unaware friends also expressed unease when seeing the threatening silhouette, a disturbing reminder of the ongoing unrest.

Having been in contact with mercenary combatants in Afghanistan, Emeric knew what he was talking about when he told his story. Paid soldiers are aware that the sight of conflict triggers fear, he had said; they exploit this fact to increase their demand, relying on the media who readily stages conflict to increase their audience. Politics, Rancière points out, “is not the art of governing, it is first of all the inscription of the common in the realm of the sensible” (82). Lhuisset’s “mercenary corporation” extended this appreciation to the domain of our military system, especially when contemplated in the framework of its intimate relationship with economic interests. What Rancière says of politics also applies to the security sector, whose role appears to be the opposite of the art of protection, for it justifies its existence through the propagation of fear and the mediatized trade of violence. Emeric’s data verified. Deploying armed forces in the city did not stop the threats that would soon escalade. The soldier’s silhouette pasted on my wall did not stand for safety but was instead a flag signaling the flaws of our protection system. A shadow should not be read as presence but rather as a void, a dark side that signifies the precarity of our representations of the world.

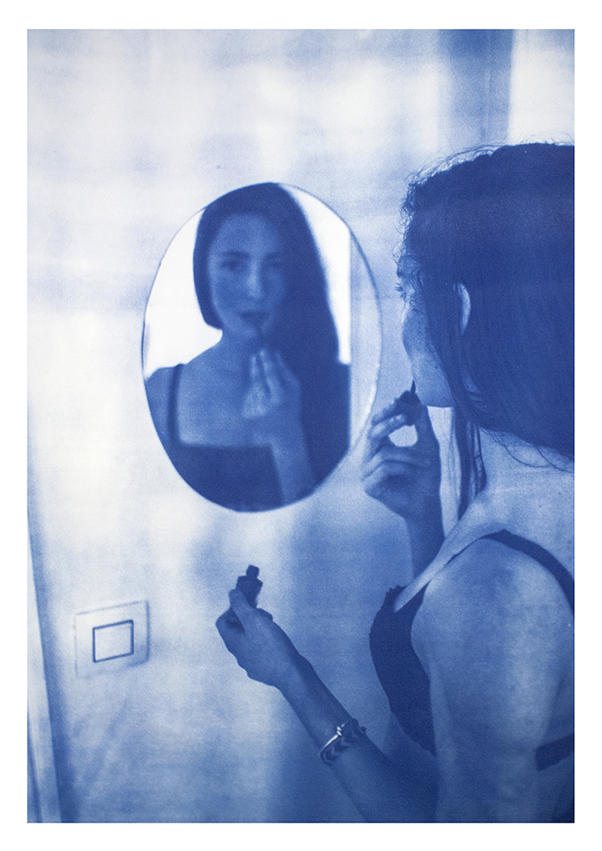

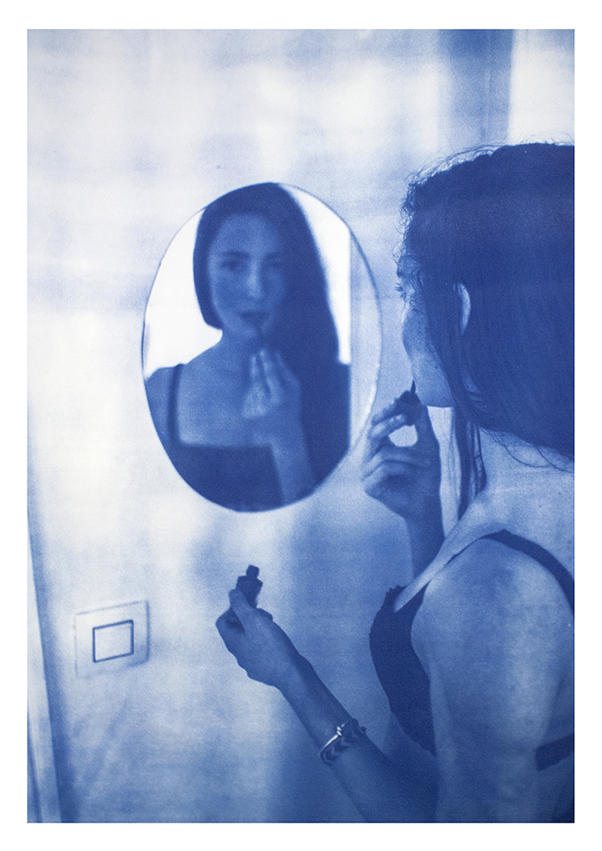

In the same vein, although via a different strategy, Figure 2 stages a disappearance to better reveal the true meaning of the image. Unrelated otherwise, Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 are therefore linked by the activation of a visual ruse that I will call Lhuisset’s trick or trap, which entices the viewer into the frame only to reveal a more complex truth than originally perceived. This strategy forces the viewer into a reading of the image where its political dimension cannot be ignored. Figure 2 belongs to L’autre rive, a project gathering 43 cyanotype handmade prints of photographs taken by the artist between 2011 and 2017 in several countries where he travels often (Iraq, Syria, Turkey, Greece, Germany, Denmark, France). The pictures have no title, but when talking about them, the artist refers to them by the name of person in the photograph; for the most part, they are his friends. The project began when Lhuisset decided to do a work on the refugee crisis, with the desire to change its “face,” systematically degraded by those who had been generating its visibility. Lest we forget, oppression begins with the “impossibility of seeing oneself in a place other than the one in which one has been put” (Rancière 81). Those who had to flee their home country already saw themselves in a terrible situation, but the press and the artworld would “put” them in an even worse place by flaunting the humanitarian emergency with shameless opportunism. Through the images that circulated in journalistic and artistic venues, the figure of the refugee was stereotyped, dehumanized, spectacularized, and overall manipulated for political or economic interests. Indeed, “some of the most significant insights into global politics emerge not from endeavours that ignore representation, but from those that explore how representative practices themselves have come to shape political events.” (Bleiker 261). Lhuisset’s intention to restore the perception of the refugee and to rehumanize them through the restoration of their visual image responds to that agenda. Although it is not the role of the artist to change the world, he claims, artists do have a duty to act responsibly within the public sphere they occupy,

To launch the project, Lhuisset headed to Lesbos, the entry point to continental Europe for countless refugees. An unforeseen event reoriented his plans: his close friend, Kurdish fighter Foad, who was to join him in Lesbos, perished while attempting to cross the sea from Turkey. L’autre rive thus became a tribute to Foad, who tragically disappeared. The series includes an image of sea water, the only visual element evocative of the tragedy. A selfie of a confident Foad standing on the Turkish coast, sent to the group prior to embarking, opens the series. L’autre rive is presented as a visual journal documenting the artist’s friends, who happen to be refugees. The images steer away from their dramatic flight or the reasons that might have motivated it and focuses exclusively on the sites they remember and on their new lives. If not for the banality of the scenes, it could be considered a celebration of their victory over death. It would not be an exaggeration. The choice of subjects is not anodyne, for the familiarity between the photographer and the photographed is perceptible in the photograph. The viewer is invited to share the quiet intimacy and uneventful quotidian of Emeric’s friends. Nothing in the image indicates their refugee status, sometimes clandestine.

L’autre rive is structured in three phases, the first one centred on landmarks in Lesbos, described by those who went through the island. The second phase sees Emeric’s friends already migrants in Europe, engaging in daily routine in different countries. The third phase, where Figure 2 (Ines) belongs, follows the children of older refugees, European nationals going about their business. I could have chosen any picture, but I selected the one of Ines because I was attracted by the mirror, one of the oldest means to catch the world’s visualness and an art historical reference of lasting success. The image shows a young woman in a private setting while she puts on make-up. Ines is the daughter of an Algerian refugee; she holds French citizenship and works as a journalist. The artist invited her to take part in the project because he wished to include a success story in the series. The stereotype of failure often slapped on immigrants needed to be countered. Ines is photographed from behind, but the mirror in front of her creates a three-dimensional view of her figure, allowing her gaze to meet ours. A certain sensuality emanates from the scene, engaging the viewer. The setting suggests a bathroom; maybe she just stepped out of the shower, which would explain why she is lightly clad. But her semi-nudity has a different purpose, which also elucidates the angle of the picture. Upon closer inspection, we notice her upper arm appears odd, somehow disproportionate. One would never guess that it’s the trace of an old wound, left from several bullets she took while sitting in a terrasse during the November 2015 Paris attacks.

If an uninformed spectator would come upon this image, they would probably not recognize its underlying violence. In fact, all the images in the project transmit a placid banality, rendered even less exalting by their monochromatic nature. L’autre rive tells a saga, but without a narrative to accompany the images, its details are lost. Context is important in most viewing experiences; in this case it appears essential. Perhaps it’s not the artist intention to tell individual stories, however, perhaps his project aims to document the collective act of a humanitarian crisis, one that has no beginning and never seems to never stop. Formal elements in the project and its configuration appear to corroborate the latter interpretation. The choice of color provides some clues. Blue is the color of the European Union, the other side evoked in the title of the series, the future country of the New Europeans. It is also the color of water, acting as a metaphor of the sea where so many disappear. As Foad, engulfed by the sea, the images in the series were programmed to meet the same fate. As we will recall, the artist modified the chemical process of the cyanotype paper used for these prints to keep the image from being “fixed.” As soon as the prints were exposed for viewing, the images began to disappear. They became solid monochromes with the passage of days. With the images gone, a blue void appeared; Foad, Ines, and the others were thus freed, not from their condition, but from their representation. Lhuisset’s cyanotype monochromes reminded me of Yves Klein’s passion for this color. Blue, “the invisible becoming visible” received of the firmament and leading to the immaterial dimension. We must not be fooled by the materiality of Emeric’s works, for if we admit that what he ultimately shows are “visual manifestations” of geopolitical analysis, we might say that, like Klein said of his paintings, his works are but “ashes” of his art. What is shared and distributed are not only the images he presents but the human weight of those that inspire them. The sensible is path the political.

Going to an exhibition of Emeric Lhuisset predisposes viewers familiar with his work to a politically imbued experience, but even the uninformed will experience the power of his subterfuge and fall into his trap. The artist likes to cite Rimbaud as one of his references, recognizing in his poem “Le dormeur du val” (Annex) the “trick” he uses to attain his objective, which is to entice the innocent viewer with the promise of an idyllic journey and then, once they are in, let them follow the path into the realization that they will reach an unexpected destination.

.

Figure 1. Emeric Lhuisset – Mercenary International Corporation (silhouette).

NB: Unable to find a picture of the work discussed in this paper (“my” soldier), I came across this one in the internet. Its physical location is the Ecole national des beaux-art, Paris. This image is used in an article about private military security and mercenaries (Sherwood, 2009), without the artist’s knowledge or authorization

By Rose Marie BARRIENTOS

Pluton-Magazine/Paris16/2021

Rose Marie Barrientos is a Bolivian art historian, lecturer and writer. She completed her studies in France (Sorbonne University), where she co-founded Art & Flux, a research platform on the relationship between art and economy, her field of expertise. She is currently completing a PhD in Argumentation Studies at the University of Windsor, Ontario – Canada.

.

.

.

.

References

Azoulay, Ariella. “Getting Rid of the Distinction between the Aesthetic and the Political.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 27, no. 7–8, Dec. 2010, pp. 239–262, doi:10.1177/0263276410384750.

Bleiker, Roland. “In Search of Thinking Space: Reflections on the Aesthetic Turn in International Political Theory.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies, vol. 45, 2, 2017, pp. 258–264.

Dagen, Philippe. “Notes sur les travaux récents d’Emeric Lhuisset.” Arte TV (Documentary 7″23, 2015, www.emericlhuisset.com/demarche14.html

Elcheikh, Zeina. “Fading Photos and Stories of Conflicts. An Interview with Emeric Lhuisset.” Visual History, 15 January 2020, www.visual-history.de/en/2020/01/15/fading-photos-and-stories-of-conflicts-emeric-lhuisset/

Rancière, Jacques. “Esthétique de la politique et poétique du savoir.” Espaces Temps, 1994, pp. 80-87, www.persee.fr/doc/espat_0339-3267_1994_num_55_1_3910

Salmon, Loic. “Mercenariat : de l’action militaire à la sécurité.” Association nationale des Croix de guerre et de la Valeur militaire, 25 April 2012, www.croixdeguerre-valeurmilitaire.fr/2012/04/25/mercenariat-de-laction-militaire-a-la-securite/

Sherwood,Ross. “L’essor des armées de mercenaires : une menace à la sécurité mondiale.”The Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG), 15 September 2009, www.mondialisation.ca/l-essor-des-arm-es-de-mercenaires-une-menace-la-s-curit-mondiale/15223

Toma, Yann and Barrientos, Rose Marie. Les entreprises critiques: la critique artiste à l’ère de l’économie globalisée. Cite du design, 2009.

Vihalem, Margus. “Everyday aesthetics and Jacques Rancière: reconfiguring the common field of aesthetics and politics.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, vol. 10, 1, 2018, doi:10.1080/20004214.2018.1506209

Appendix 1

Le dormeur du val

It’s a green hollow, where a river is singing

Crazily hanging on the grasses rags

Of silver; where the sun, from the proud mountain,

Is shinning: it’s a little valley bubbling with sunlight.

A young soldier, his mouth open, his head bare,

And the nape of his neck bathing in cool blue watercress,

Is sleeping; he is stretched out on the grass, under the skies,

Pale in his green bed where the light falls like rain.

Feet in the gladiolas, he is sleeping. Smiling like

A sick child would smile, he takes a nap:

Nature, rock him warmly: he is cold.

Fragrances do not make his nostrils quiver;

He sleeps in the sun, hand on the breast,

Peacefully. He has two red holes in his right side.

Arthur Rimbaud, Poésies, 1870

Ttranslated by Camille Chevalier-Karfis

[1] Joseph NicéphoreNiepce produced the first permanent image using a camera obscura and paper coated with photosensitive chemicals around 1816. Innovations followed form his collaboration with Louis Daguerre, who invented the daguerreotype in the early 1830’s. In 1888, Eastman introduced the box camera. https://web.archive.org/web/20080213170459/http://www.photography.com/topics/history-of-photography/

[2] Website of the artist http://www.emericlhuisset.com/demarche14.html

[3] Artworks created as a corporate structure, identified as “Critical Companies” (Toma and Barrientos)